The Jewish Memorial in Berlin and Memorial Center Camp Westerbork:

A Comparison

Introduction

This paper is written as a final product of my participation in the course Exploring Berlin Museums, provided by Victoria Bishop as part of the HUGS international courses of the Humboldt University of Berlin. I have attended this course in the summer semester of 2021, taking place from the 15th of April until the 15th of July. The goal of this paper is to demonstrate the process of anthropological research, in the context of the subject that have been treated during the course, mainly focussing on the various ways in which the Jewish community is represented through memorials and museums. As such, I have chosen to compare the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin – which has been featured prominently during the course – with the Memorial Center Camp Westerbork (which I will refer to as “Westerbork”), mainly focussing on the monument of the 102,000 stones. I will assume familiarity with the Jewish memorial in Berlin to the extent it has been covered within the course, allowing me to feature more background information about Westerbork.

History and Background

The Memorial Center Camp Westerbork is located in the province of Drenthe, in the northern region of The Netherlands. The name of the site refers to its role in the event leading up to – and during the second world war. Initially built in 1939 as a camp for Jewish refugees that had fled across the nearby German border to escape the Nazi regime, it later became known as “the gateway to hell” in the function of a transit camp during the German occupation of The Netherlands. On the 13th of September 1944, the last train departed from Westerbork, carrying 279 of the more than 100,000 people that were transported east during this macabre era in the lifetime of the camp. Of these people, most were Jewish, with the remainder being made up out of Sinti, Roma and a handful of resistance fighters. As marked on the map in Figure 1, the majority of the trains set way to Auschwitz, a smaller part to Sobibor, Theresienstadt and Bergen-Belsen. Only 5,000 returned.1

Present Day

After the end of the second world war, the site of the camp kept playing a prominent role in local history. It has been used as a prison for Nazi-collaborators before returning to its original role as a refugee camp, this time for refugees originating from the former Dutch colonies of the West-Indies. However, during the present day the site is mainly used as a memorial center, housing educational exhibits on its history and monuments in honor of the various groups of people that have been interred in the camp during the second world war.1

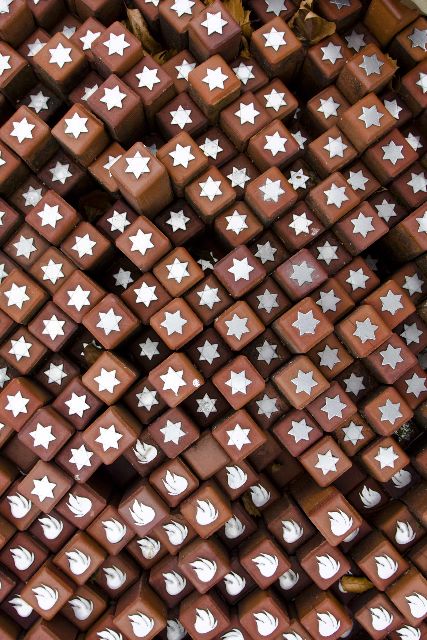

A notable monument within Westerbork is that of the 102,000 stones, located at the former main square of the camp. The monument pays tribute to the people that were deported via the former transit camp in the form of small stones, each representing a single person. Most stones are marked with a symbol: a star of David or a flame, as seen in Figure 2. The stones differ in height throughout the whole monument. Paths separate different patches of stones, allowing visitors to walk in between. Together with the tiling of the surrounding area, the stones take the shape of (the European part of) The Netherlands (as seen in Figure 3).2

Reflection

The Memorial Center Camp Westerbork takes up a prominent place in my youth, especially within the process of becoming aware of the atrocities of the second world war. Being born and raised in the northern part of The Netherlands, Westerbork was the largest and most prominent reminder of the holocaust in my vicinity. More than once, my parents have taken me along to the yearly remembrance ceremony on the 4th of May, hosted on the grounds of Westerbork. These ceremonies also feature prayers and monologues, spoken in Yiddish by a Rabbi, which has made me aware of Jewish culture at a young age (especially given the fact I am not of Jewish descent myself). Being introduced to the Jewish Memorial in Berlin during the course, I was immediately taken back to the memorial of the 102,000 stones. To me, this association seems obvious: both monuments are in reference to the events of the holocaust and feature a manifold of stones (albeit at very different scales). However, while diving deeper into the possible meanings of the monument in Berlin, I felt like the similarities became less. To investigate whether my initial feeling of resemblance was justified, I have chosen the comparison between the monuments as the subject of this paper. Regarding my own bias towards this subject, I do notice that I have some emotional feeling towards my findings. As stated before, I consider Westerbork to play a somewhat significant role in my upbringing, which might bring me to overstate the significance of the site on a larger scale. I do not have such an emotional connection with the Jewish Memorial in Berlin. This feeling might be enhanced by an “underdog effect”, where I subconsciously want the smaller, rural memorial of Westerbork to hold up against the grand Jewish Memorial in the big city in terms of depth and sophistication. All of this should be considered when reading my impressions and findings.

Impressions

Both Jewish memorials in Berlin and Westerbork implicitly reference the number of victims to the holocaust. Whereas the designers of the Westerbork monument actually made an attempt to have it feature as many stones as victims, this was not the case in Berlin. The monuments do differ in several interesting ways. In Berlin, the monument towers over its visitors, making them feel small and conveying the impact of the holocaust. In Westerbork, the monument is relatively small, with the stones reaching knee-high at most. However, the stones form a map of The Netherlands, relative to which, if scaled up to the size of the actual country, they are enormous. The scope of the Berlin monument is in different from that of Westerbork. The Berlin monument has a very explicit focus on the Jewish population in Europe that have lost their lives during the holocaust. The Westerbork monument also represents Jewish people, although only those that have passed through the transit camp, as well as Sinti, Roma, and others. A number of stones have emphatically been linked to one of the groups that are remembered. This is done using a symbol representing the group (a star of David for Jews, and flame for Sinti or Roma) or no symbol at all (any other group, for example resistance fighters). This makes the monument more personal, but also limits the room for interpretation by visitors when compared to the more ambiguous monument in Berlin. All in all, the atmosphere at the Westerbork is also very different from that at the Berlin monument. The choice of colors, symbolism and size give a much “lighter” feel than the dark monoliths in Berlin. This raises the question of what has led to this difference in approach, and weather either monument could have been build at the other location.

Future Research

To investigate the motivations behind the monuments and the attitude of its visitors towards them, more in-depth research is required. In the limited available time of writing this paper, I have not been able to find interviews with the designers of the Westerbork, making it difficult to assess their intentions. If such a resource could be found, it could be compared to the many interviews with architect Peter Eisenman, responsible for the design of the Jewish memorial in Berlin. Even more interesting is the effect of the memorials on their visitors. Does it match the intended effects, or do the visitors give their own meaning to the installations? This information can be gathered by conducting interviews with visitors, during which they are questioned on their interpretation of the symbolism of the memorials. Especially the interpretations by the locals are of interest, since they give insight in the motivation behind the selection of the monument design by those that have commissioned it.

Discussion

One can speculate that this difference in approach in memorializing stems from a difference in attitude towards the holocaust. Where the German attitude is characterized by a feeling of guild, the Dutch mainly represent themselves as victims. This allows for more identification with the victims of the holocaust, something that is emphasized by the shape of The Netherlands being incorporated in the monument: the victims are The Netherlands. Instead of identifying with the victims, the German monument appears to be more imposing and threatening, but most of all very ambiguous. Its ambiguity was intended by architect Peter Eisenman, which is the polar opposite of the symbolism that designers J.A. Gilbert and P.A. Ritmeijer have incorporated into the design of the Westerbork memorial.3 Ultimately, the differences in character of the monuments do seem to suit their respective locations. Both approach remembrance of (parts of) the same event in very different ways, but interestingly do so using similar concepts.

-

History. Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork. Visited on July 7th, 2021. ↩↩

-

Hooghalen, “De 102.000 stenen”. Het Nationaal Comité 4 en 5 mei. Visited on July 7th, 2021. ↩

-

Peter Eisenman: Designing Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial. Eric Baldwin. April 26th, 2020. Visited on July 15th, 2021. ↩