The Academic-Industrial Dichotomy

In this paper, the dynamics of academia and industry are explored on the basis of the case of the former airfield Johannisthal-Adlershof area and academia in Berlin, exemplified by the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin (HU). This case shows how emerging industry and new scientific disciplines can grow towards each other, and share resources to form a prosperous symbiosis. Nonetheless, the commercial interest of industry put pressure on the academic freedom of the university in this relationship. Whether the goals justify the means is not a question to be answered in this paper, but some ideas are put forward that might leverage the loss of academic freedom, such as finding a broader range of partners beside commercial organizations. By ensuring a spectrum of motivation among the partners of the university, the university can find solid footing to protect the academic freedom of its researchers.

Introduction

More often than not, academia and industry are presented as two opposing forces in society. Students are presented with a choice: contribute to your domain of science by staying in the academic world, or apply your knowledge and monetize it by entering the industry. This is, of course, an exaggeration of reality. However, it is unclear what reality actually looks like in this case. It is easy to assume that these two worlds are opposing, with conflicting ideologies. The same can be said for the reverse, where academics and industry form a symbiosis. In the latter case, interesting questions arise on the academic freedom that academicians have if their work is influenced by the industry. In this paper, I aim to paint a picture of a dichotomy of academics within Berlin — specifically the HU — and the industrial area of Adlershof and the former airfield Johannisthal.

My approach to describing the relation between the HU and the industrial area is as follows. First, I will provide a short history of the airfield Johannisthal and Adlershof, which led into the development of the industrial area. Next, I will argue why this specific case is a good example of the dynamics between academia and industry. Finally, I will draw some conclusions about the dichotomy of academia and industry in general, based on the literature research I have done in the earlier sections. Here, the main focus will be on the implications on academic freedom as a result of industrial and academic cooperation.

This paper is written as the final assignment for the course Philosophy in Berlin: Academic Freedom in Practice, which is part of the HUGS program at the HU. During this course, several aspects of academic freedom have been explored, especially in relation to significant philosophers and other figures that were active in and around Berlin. As such, the subject of this paper also deals with academic freedom. A final personal note on my motivation to research the case of this study. Upon arriving in Berlin, I have become intrigued by the history of the former airfield Johannisthal. Living in the adjacent Adlershof borough, I have been confronted with the many traces it has left in the area. For this paper, I saw an opportunity to combine this interest with a choice I am currently presented with at the end of my master’s: academia or industry?

A Brief History

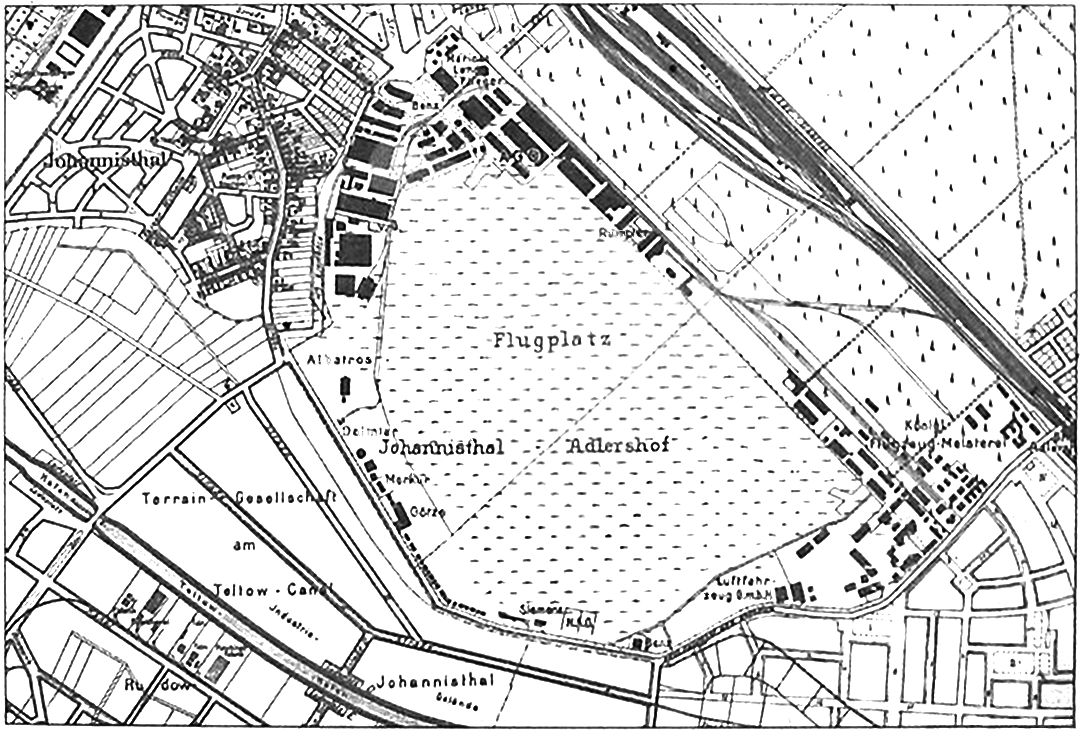

Airfield Johannisthal was founded as the second airfield in Germany — and the first for motorized aviation — on September 26th, 1909.1 The area that was chosen was located between the Berliner suburb of Johannisthal and the neighboring village Adlershof, nowadays, a suburb of Berlin as well (see also Figure 1). With the invention of the airplane occurring only years before the founding of the airfield, the aviation industry still had a lot of room for innovation and development. As such, many pioneers and companies found their way to the site, trying to tap into new ways of monetizing this new technology. Innovators, aviators and entrepreneurs formed collectives, such as the Deutchers Aero Club (DAeC) and the Deutsche Versuchanstalt für Luftfahrt (DVL).13 Over the years, the area has attracted many other industries as well, ranging from television and movie studios to car manufacturing.3 The common denominator between these industries was that they were new and innovative. During the first world war, the area contributed heavily to the strength of the newly founded air force of the German military.1 With the development of aviation technology being prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles until the 1920s, industry shifted to automobile manufacturing and the production of feature films.3 The Second World War saw the airfield returning to its original purpose of warplane production.3 Many of the technologies and infrastructures developed there were moved to the USSR in the aftermath of the war, as the Russian regime gained control of the area.13 In the 1990s, the Berliner Senate made the explicit decision to integrate science and business within the area of Adlershof.4 As a result, six institutes of the HU have been relocated to the area: geography, chemistry, computer science, mathematics, physics and psychology. The aim of this decision was to allow collaboration between academical and commercial research institutes while making use of the same infrastructure that is present at the site.25 The particular domains in which the faculties that were moved to the area operate where chosen to honor the history of the site, as well as make use of the many facilities that are there due to its history. As such, activities at the former airfield Johannisthal and Adlershof have all been in the domains of natural sciences and engineering since the 1910s onwards.

In the campus area around the shared border of the former airfield Johannistahl and Adlershof, two worlds meet. The area provides a good example of the relations between industry and academics. Here, science is conducted both by the HU and commercial organizations. Looking at the dynamics found on the site, some ideas about the benefits and costs of having such intimate relations between industry and academics can be hypothesized. In the remainder of this paper, I will evaluate these relations and theorize upon their implications (especially in the context of academic freedom).

Analysis

As mentioned before, the fact that industry and academics operate in proximity allows for a shared infrastructure and the exchange of knowledge.5 The rapid (planned) growth of the number of facilities and institutes at the site indicates that the ecosystem that has been created thrives.4 One can only speculate whether this is a result of moving part of the HU to this location, or that this move was in itself triggered by this growth. Nonetheless, it is safe to say that the presence of HU facilities has enabled larger investments into the area by the HU itself. Additionally, the HU (as well as the presence of a student village) has ensured a constant influx of students who take part in internship and other projects hosted by industry on the site.2 With over 500 technological companies located within the area, the options for gaining experience and monetizing knowledge are much greater than compared to a situation in which a university is isolated from industry.2 This relationship embodies the very definition of a symbiosis, as the industry is provided with new talent and a constant push for innovation, while the university becomes more attractive to students that want to be exposed to potential employers. With more students and personnel, the number of projects being worked on can be enlarged.

Looking at this seemingly successful symbiosis of industry and academics raises the question: at what cost? Ideologically speaking, industry and academics have vastly different motivations behind their activities. The prior develops and innovates out of commercial interest, turning an investment into profit, while the latter conducts science with the goal of gaining and spreading knowledge for the sake of science itself. This is of course only the case in theory, as many universities have also become more conscious about commercial interest when deciding upon research projects to conduct. Vice versa, businesses can also have ideological motivations, causing them to give up some of their profit in favor of attaining some other goal. Still, the difference between the two is there, as can be observed in the fact that the HU is active in a broader domain than the industry found at Adlershof. Many other faculties do no have such a close proximity to industry, if an equivalent industry exists at all (most of the principal conglomerates have yet to establish a department of philosophical research and development). If the university was motivated by commercial interest alone, these faculties would not persist. Evidently, tightening the ties with commercial partners can put pressure on the main ideology of academics. In order to maintain the interest of the industry, projects being worked on in cooperation must have some relevance to their commercial goals. This limits the scope of the activities that researchers at the university can undertake. On the long term, this will mean that commercial value determines the direction in which knowledge is developed, leaving avenues that might contribute to improvement along different metrics unexplored.

Conclusion

The balance between cost of integrity and benefit of progress is a delicate one for the dichotomy of industry and academics. On the one hand, industry allows universities to delegate activities and to provide their students with practical experience. However, the commercial interests of the industry can put pressure on the academic freedom of academics, as the university will be tempted to favor research that lend themselves better for monetization. Without support from industry and thus without support from the university, a researcher will find it difficult to explore novel areas of interest. Still, in a world that favors the quantization of progress and productivity, commercial gain is a metric that is easily accessible and understood. To counter this trend, other metrics are needed to evaluate the work produced by researchers. Given the fact that the commercial metric does propel academic progression in certain domains, it is by no means said that it should be abandoned altogether. However, to gain progression in other domains as well, universities will either have to cooperate with non-commercial organizations (e.g. the state or non-profit organizations), or apply the commercial gains on the one side to support research on the other. Just as is the case with commercial partner, non-commercial partners will have their own pitfalls. However, it ensures that the university is not dependent on commercial gains alone, making it possible to demand more academic freedom from all partners in all domains.

-

100 Jahre Innovation aus Adlershof. Wiege des deutchen Motorluftfahrt. 2009. ↩↩↩↩

-

Geschichte. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. 2017-06-29. ↩↩↩

-

Zeitreiseziel Adlershof. Von Aktueller Kamera zu Anne Will. WISTA Management GmbH. ↩↩↩↩↩

-

Adlershof. Bezirksamt Treptow-Köpenick von Berlin. ↩↩

-

The Adlershof Campus. Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. 2015. ↩↩